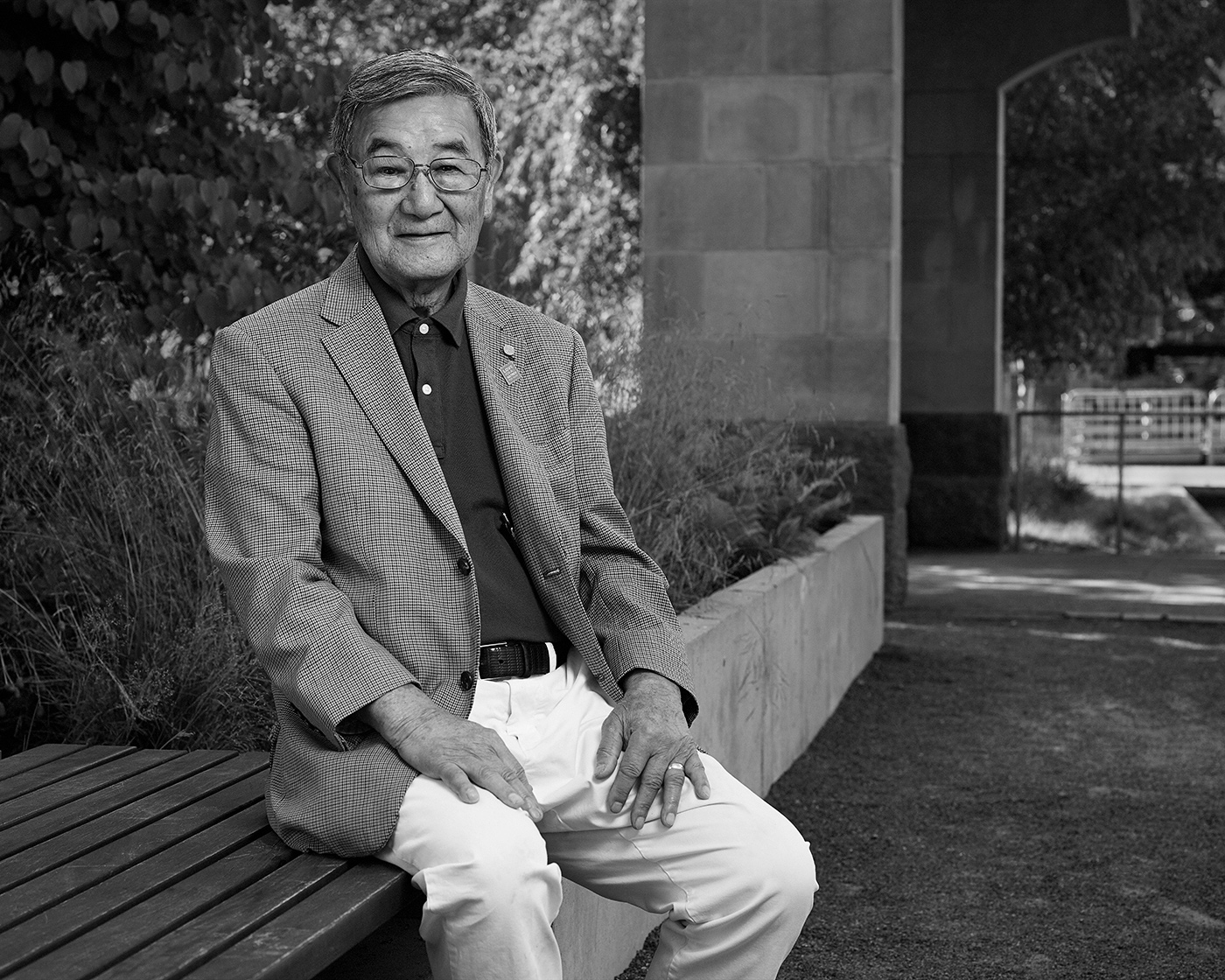

Katy McCormick received an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is an artist and educator based in Toronto, where she teaches photography, book arts, and documentary studies at Ryerson University. Her project Rooted Among the Ashes: The A-bombed Trees of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, will be presented in 2021 at the Harry S. Truman Library & Museum, in Independence, Missouri. She is a member of the Atomic Photographer’s Guild. She joined the HNDC in 2017. katymccormick.com

Katy McCormick

“I was an American standing at ground zero and somehow until that moment I really had no idea what Hiroshima meant.”

I first arrived in Hiroshima on August 5, 2008. At 8:15 the following morning, I was part of the assembly gathered to commemorate the sixty-third anniversary of the atomic bombings, held in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. I was jet-lagged, disoriented by the chorus of cicadas, and dripping with sweat. A dawning realization of what had taken place there sixty-three years earlier made me weak in the knees. I was an American standing at ground zero and somehow until that moment I really had no idea what Hiroshima meant. I began to imagine the horrors as I stood shoulder to shoulder with those around me. Three days later, on August 9, I stood again at ground zero—this time in Nagasaki. Again, I was overwhelmed, guilt-stricken, and thinking: “My people did this to your people.” To my amazement, no one directed any hostility or resentment toward me.

I could not anticipate how powerful those experiences would prove to be. I only knew that the effects of a uranium bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” and a plutonium bomb called “Fatman”—highlights of American technological achievement—were no longer abstract facts. I knew that the veneer of “that was then” no longer held. I began to imagine what little girls and teenagers, mothers and babies, and old men and women faced without warning: FLASH, BLAST, FIRE, BLACK RAIN, RADIATION—in an endless spiral of death and destruction. As I gained new knowledge about weapons of mass destruction in subsequent research, I realized that I needed to understand how these events occurred. My questions poured forth: What makes atomic bombs different from all previous weapons? How do bombs “save lives”? Why had I learned so little about the human impacts of nuclear weapons? Are weapons of mass destruction keepers of the peace?

My first journey to Hiroshima and Nagasaki redirected the focus of my art and research. By 2013, they were at its core, as I undertook creative projects exploring their landscapes, archives and survivor narratives. These filled artist books, experimental films and large-format photographs. My current project comprises immersive portraits of the other living witnesses of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—some six hundred years old—known as the A-bombed Trees. They stand in school yards, shrines, temple grounds, squares, and parks. They are reminders of the tenacity of life—and the centrality of trees to our own survival.

—Katy McCormick