Ariel: Tell me about your students. Why do they come here, and what do they have in common?

Hugh: Well, originally, the focus of the school was to bring dropouts back into school.

Jeff: We were open to adults. That was before the Harris years.

Hugh: I remember having this guy who was thirty years old in my grade 11 math class.

Claire: I had guys in their forties.

Hugh: Things have changed a lot. We’re no longer able to take students over twenty-one years old, which has changed the nature of the school quite a bit. There used to be more of an emphasis on social justice. The type of student coming in is different, younger. Over the past half-dozen years, we’ve seen a huge spike in the number of kids who have issues with anxiety and depression, so trying to cater to them becomes more of a focus.

Hugh: Things have changed a lot. We’re no longer able to take students over twenty-one years old, which has changed the nature of the school quite a bit. There used to be more of an emphasis on social justice. The type of student coming in is different, younger. Over the past half-dozen years, we’ve seen a huge spike in the number of kids who have issues with anxiety and depression, so trying to cater to them becomes more of a focus.

Claire: Since Mike Harris, the rule has been that if a student turns twenty-one during the school year, and they haven’t finished high school, at the end of that year they have to go in Adult Ed. Before Harris, they had a choice. Actually, in my first year here I taught a guy I’d gone to high school with. He wanted to go to OCAD and needed to upgrade his credits. You’d think that would be a very awkward situation, but it wasn’t. It was actually really kind of interesting.

When I first walked into the school, it looked like Woodstock. It was all Deadheads and Phish jackets. I mean, the hippie look was a past thing, even when I came of age. It was like a group Halloween costume, but these guys were for real. It was a hippie school.

Hugh: Yeah.

Claire: And they’d all disappear. Suddenly, you’d come in and no one was here if the Grateful Dead were playing anywhere within a three-day car trip. They’d be gone. I had a few students in the early days, when we taught adults, who had come right out of prison in Kingston and wanted to go to university. We’d also get some immigrants, like the guy who had just moved here from Nigeria who was forty. There was that guy who was in his seventies, who would just come and take classes for fun. It was actually kind of neat. It was very interesting to have that mix of ages.

Jeff: The other thing that’s changed is that what used to be much more of an academic, straight-to-university focus has become, in the last ten to fifteen years, much more of a balance between college-bound and university-bound students. Our clientele seems to be different in terms of what they need. It’s changed over time.

Jeff: The other thing that’s changed is that what used to be much more of an academic, straight-to-university focus has become, in the last ten to fifteen years, much more of a balance between college-bound and university-bound students. Our clientele seems to be different in terms of what they need. It’s changed over time.

Sean: I’m actually not staff here. I’m essential board staff, and I travel to many different alternative schools. I haven’t been here for long, but I think this is a discussion that’s happening at many schools; they’re seeing the demographics of students change. How do alternative schools absorb that change? Do they try to change the students to match the philosophy of the school? Or do they now change the school to match the students? Do they stay true to their foundational ideas, or do they constantly evolve? That’s the discussion that happens in every classroom that I’m in, every day of the week.

Ariel: One thing that I find super interesting about THESTUDENTSCHOOL is your mentoring program. Tell me how it works and how it came to be.

Beth: I’m not sure how it originated. Eighty-five to ninety percent of our students are new every year. So, what we do is divide up that list between all the staff members. Students can choose whom they would like, or I read all their entrance documents, and I try to match them with the person who I think would be best. And then the teacher and student meet five times throughout the semester. The nature of those meetings varies based on the student’s needs. It can’t simply be just a check-in. Because we’re now dealing more with people with mental health issues, then the meetings can focus on anxiety reduction or things like that. And also, because the students are almost all new, it’s a chance for us to go through their entire school record and talk about what they’re planning on doing and how we can facilitate that.

Beth: I’m not sure how it originated. Eighty-five to ninety percent of our students are new every year. So, what we do is divide up that list between all the staff members. Students can choose whom they would like, or I read all their entrance documents, and I try to match them with the person who I think would be best. And then the teacher and student meet five times throughout the semester. The nature of those meetings varies based on the student’s needs. It can’t simply be just a check-in. Because we’re now dealing more with people with mental health issues, then the meetings can focus on anxiety reduction or things like that. And also, because the students are almost all new, it’s a chance for us to go through their entire school record and talk about what they’re planning on doing and how we can facilitate that.

Jeff: We have students who are applying to college or university, so that’s part of the process as well. There’s a guidance aspect to it. But often, as Beth mentioned, life issues come up, so we meet formally a number of times, but then there can be informal meetings too.

Ariel: And you both mentioned anxiety and other mental health concerns. Do you have a counsellor that comes in to work with kids?

Beth: We have a social worker three days a month, but we find, increasingly, that a lot of students, they’re not willing to meet with the social worker, but they are willing to meet with the teacher.

Ariel: So mentoring is quite important for some of them?

Jeff: Yeah.

Ariel: The school puts an emphasis on both fine arts and environmental studies. That’s a pretty interesting combination. How did that dual focus come about?

Beth: Our teacher Anita, who had been a city planner, pioneered courses in environmental studies. Then when I came in, we did school-based activities, we tried to make school as green as possible. We put in funding applications, built the pollination habitat that we have outside—a sort of outdoor classroom—and then we were involved in greening the building. We were one of the early platinum eco-schools in the Board. But we’ve found since we’ve moved to the blended learning model, it’s been more difficult to do these school-wide activities.

Ariel: Tell me how you define blended learning.

Beth: 50 percent online, 50 percent face-to-face.

Jeff: We went blended a couple years ago. You typically see your student five days a week. Now we’re seeing them in class twice a week, so it’s significantly less time. It’s more like a college model that way. Every class has a wiki attached to it. We maintain an online presence: there’s a video to watch, there’s an assignment, and then they’ll come to class having done that.

Ariel: Is that something that students are asking for?

Jeff: Some were.

Claire: Particularly, I think for a lot of the kids with high anxiety and other kinds of issues, actually coming to school is problematic. So having an online platform that got around that problem was seen as being useful.

Beth: It’s also a way to offer more classes with few staff if our student numbers are down.

Sean: We’re always in this dance with the Ministry of Education to maintain public funding. That’s one of the reasons why you’re seeing alternative schools change, because they can no longer operate under their own self-actualized rules. They have to have a certain number of students and level of attendance to maintain their staffing. Because staffing at alternative schools is so small, a single teacher’s personality can really make a stamp on the school.

Sean: We’re always in this dance with the Ministry of Education to maintain public funding. That’s one of the reasons why you’re seeing alternative schools change, because they can no longer operate under their own self-actualized rules. They have to have a certain number of students and level of attendance to maintain their staffing. Because staffing at alternative schools is so small, a single teacher’s personality can really make a stamp on the school.

Ariel: I know that when your school first started in 1979, one of its innovations was that courses were designed and planned by committees of students, teachers, and outside consultants. How do students and teachers work together these days to determine course offerings?

Hugh: What we’ve always done is give students input into what courses we teach. We have a survey that they fill out. We use that data to put together a timetable that fits most people’s needs. It gives the students some ownership. Right now, we’re working on putting that online. One thing that’s been very successful about our shift to blended learning is communication. You can communicate with students through either text or email, and they’re more likely to hear about what’s going on and more likely to come back, because as with all alternative high schools, there’s usually a very significant dropout problem; online learning helps to curb that.

Ariel: You also have a substantial art program, and I noticed on your website that there’s been an increasing demand for technical art courses. Tell me about the interplay between studio and technical courses. How do those two things fit together?

Jeff: Adam teaches most of our tech courses. Maddie is our art teacher.

Adam: I think it is great that we have such a large arts program, because the students can explore how art and technology relate to one another. Though the technology courses that I teach have an artistic aspect, like colour theory, for example, that’s not part of the curriculum. At my old school, an academic school in Scarborough, the majority of students who took my tech courses were not at all interested in art.

Adam: I think it is great that we have such a large arts program, because the students can explore how art and technology relate to one another. Though the technology courses that I teach have an artistic aspect, like colour theory, for example, that’s not part of the curriculum. At my old school, an academic school in Scarborough, the majority of students who took my tech courses were not at all interested in art.

Jeff: For a pretty small school, there’s a lot of art classes, right, Maddie?

Maddie: Ceramics, tech photography, art photography, fashion, and drawing. We try to look at art like therapy more than anything. If students are taking a whack of academic classes, they can come into art class and get a little bit of peace of mind out of it.

Maddie: Ceramics, tech photography, art photography, fashion, and drawing. We try to look at art like therapy more than anything. If students are taking a whack of academic classes, they can come into art class and get a little bit of peace of mind out of it.

If they want to tweak assignments, they can. They still have a prescriptive list of assignments that they’re supposed to do, but that’s where the alternative part comes in. If they say, “Do I have to do this in this style?” I say, no, you could do it in this style, but I still need you to do this size, and I still need you to do it in this medium. Some kids come to class that aren’t even in the class, and they just sit there and make things. It’s a little bit of a respite from the academic world. We have students who approach art in that way but we also have a lot of students who do want to go to OCAD and Ryerson and York for art, so right now we’re working on portfolios.

Adam: Yeah, and we often have kids who will take virtually every art course that is offered.

Ariel: We’ve talked to all of the teachers in our project about pedagogy, and we don’t necessarily have to look at that in that formal way, but how did each of you come to alternative education, and what kind of philosophy do you bring to it?

Jeff: I was teaching at a mainstream school, and then, this job opened up at an alternative school, and I’m like, “Okay, I’m working there.” That was it for me, but once I joined the school, I found it a very appealing program: the teachers and staff and how much they cared for the students and their approach to education and to the kids, putting kids first. And social justice, peace, it all sort of works well with my personal philosophy. I’ve been here twenty years now.

Ariel: Let’s take a side road, because that social justice piece is pretty intriguing. On your website, you talk about opening up the experience of activism. How does that happen at this school?

Jeff: We’ve been experiencing some challenges in that respect, just because of the new blended learning model. One of the benefits of the old model is that you saw the kids more frequently. We had some pretty active committees that met weekly. We had a social justice committee that was in place for years and years and years, and that hasn’t been as active lately, unfortunately. We’ll see if we can get that reinvigorated. There were a lot of kids who just would come to a meeting, and they’d bring issues and talk about them, and often take action on them. It wasn’t unusual for us to have kids go in to protests and to write letters and to bring issues to our weekly all-school council meetings. They would educate the rest of the students about a particular issue. Last year we had a motion to boycott Tim Horton’s. One of our students learned that they were using non-sustainable palm oil in their baked goods and talked about it. We’re not purchasing any Tim Horton’s for any school functions now. We’re a small school, it doesn’t make a huge difference, but I think they see that it’s a step. So that committee work is one part of social justice at the school. The other part happens in the classroom. Alex is teaching an Equity and Social Justice course, and we try to infuse every course with some activist content. We’ve made a conscious effort for a long time to do that here.

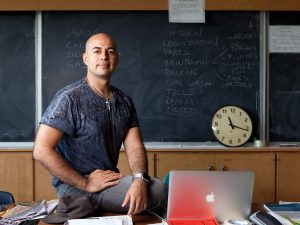

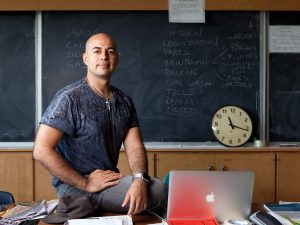

Ariel: Alex, tell me about your Equity and Social Justice course.

Alex: Sure, Equity Studies. I started at Contact in 2003. It’s one of the older alternative schools. Comes with a big history. Before that I was actually teaching self-defense, I had a self-defense business. I met a Contact teacher who said, “We’re hiring.” I went to the interview. I was interviewed by three students, two principals. I thought, “Wow, how empowering.” And much like what happens here, the students took part in running the program at Contact, in student-led discussions. Students would bring in a hip-hop artist to talk about police brutality with a lawyer. Or there’d be an anti-war activist who would come in and talk about the direct links between capitalism and war and government and how most schools are just trying to get students to become good capitalist workers and not look critically at the system. You’d be introduced to all these wonderful things. When I started in 2003, I would be at a staff meeting saying, “What a great school!” and most of the teachers would be like, “This is nothing compared to what we used to be.” And as a matter of fact, there’s been a pullback of how alternative schools are, right? If you’re looking for reasons for that, you would look at things like, our whole country has moved to the right. There have been principals, according to these longtime alt school teachers, who would bring in mainstream teachers, rather than hiring alternative teachers, trying to take away some of those opportunities for students to learn about, say, anti-war activism.

Alex: Sure, Equity Studies. I started at Contact in 2003. It’s one of the older alternative schools. Comes with a big history. Before that I was actually teaching self-defense, I had a self-defense business. I met a Contact teacher who said, “We’re hiring.” I went to the interview. I was interviewed by three students, two principals. I thought, “Wow, how empowering.” And much like what happens here, the students took part in running the program at Contact, in student-led discussions. Students would bring in a hip-hop artist to talk about police brutality with a lawyer. Or there’d be an anti-war activist who would come in and talk about the direct links between capitalism and war and government and how most schools are just trying to get students to become good capitalist workers and not look critically at the system. You’d be introduced to all these wonderful things. When I started in 2003, I would be at a staff meeting saying, “What a great school!” and most of the teachers would be like, “This is nothing compared to what we used to be.” And as a matter of fact, there’s been a pullback of how alternative schools are, right? If you’re looking for reasons for that, you would look at things like, our whole country has moved to the right. There have been principals, according to these longtime alt school teachers, who would bring in mainstream teachers, rather than hiring alternative teachers, trying to take away some of those opportunities for students to learn about, say, anti-war activism.

A lot of the teachers were really upset about the first Gulf War. They lost a lot of support from the union around teaching the connection between capitalism, militarism, and schools. All those kind of things were pulled back. There were a lot of changes that took place as far as how alternative an alternative school can be, and that you should be careful around issues like teaching about apartheid in the world. The TDSB now has very strict rules about certain countries you can’t name. I won’t name them, because we’re recording, and I know that THESTUDENTSCHOOL has actually gone through problems with that very same issue.

Jeff: Rhymes with Israel. (Laughter)

Alex: Issues around the genocide of natives, probably the worst genocide to ever take place in the history of humankind. When I’ve taught genocide courses in certain schools, we can teach about the genocide of natives. Other schools, though, you’re warned—look, the Ontario curriculum says we can talk about the Jewish Holocaust, European Holocaust, you can talk about the Turks killing Armenians, if you like, and there’s a couple other ones, but we never should, ever, talk about the fact that white people in this country were genocidal maniacs. That’s better left undiscussed. So there have been these changes, and that’s something that I wanted to share with you, because the teachers who introduced me to alternative schools, some of them would be rolling over in their graves if I didn’t.

Ariel: How do you manage to teach Equity Studies when you’re so constrained?

ALEX: Those are challenges that you face. In my thirteen years of teaching in alternative schools, I’ve taught many students from racially marginalized groups, and there are lots of challenges around how to introduce certain topics. I see a lot of pushback on gay rights. In certain racialized communities, there can be trouble with that. At Student School, we have a much more homogenous group than I had experienced elsewhere. So you might not see as much pushback, let’s say, about something like gay rights or women’s rights. When we look at our community, not all of our students come from this neighbourhood, but this neighbourhood’s very affluent. It comes with privilege. So when you ask some students to question their role in oppression, it becomes challenging for some of them.

Faced with those kind of problems in a racialized classroom, kids would explain to me what inequality is like, better than I would know. As a white man, I can do and say, I can culturally appropriate anything I want at any moment. Whereas my black students, for instance, will be like, “Alex, you’re not gonna tell me about oppression. I’m gonna tell you about it.” When you come to a more homogenous and more privileged group, the buy-in for their role in oppression is harder to find. Obviously, as a teacher, you don’t want to make them find it, but you want to give them opportunities to find those places where they can make changes in their own life, and sometimes that is challenging, to say the least.

Ariel: Does anybody want to add to that or talk about how you came here?

Hugh: I’ve taught here for a very long time as well. I teach science and some math, mostly science. I’ve always liked the idea that students here are a little more mature, and you can do some things you wouldn’t do with a less mature class. And often, classes are quite a bit smaller than in the mainstream. We’ve done a lot of impromptu field trips. We could go to curling rinks and we’d measure the angle of the rocks hitting each other. I took my class to a pool hall and did the same sort of thing. You can be a lot more creative here, and the one thing I do like about being in a small school is that I can set up things the way I’d like them to be done rather than to coordinate with a whole department.

Jeff: Hugh is the science department. (all laugh)

Hugh: We teach all sciences. We walk around the area and do geology, or walk down the Humber River. Sometimes I just take my class outside and we just look at the rocks—people’s gardens have all these rocks, and kids don’t realize that if you look at a rock, you can tell where it came from and how old it is. I like doing things that are spontaneous, and also this do-it-yourself concept that Beth has been really involved in, where you just build stuff as part of a lesson. We’ve built model rollercoasters out of scrap wood and glue. We just taught a DIY course, in fact. It’s been quite successful in getting students to do things and make stuff rather than learning only through more traditional methods.

Beth: Talking about how we got here—I came from another Board, and strategically attempted to get in Toronto alternative schools, because I was amazed. We didn’t have anything like that where I was from, so it was with great delight that I arrived here. And similar to Hugh, what I liked about it is that you are largely the generator of your curriculum—while you are aware of Ministry documents, you have a lot of flexibility in terms of how you can interpret them. So you can think about your student body and courses that will work for them. With the DIY course, I found that increasingly we had more male students than female students, and we didn’t have any tech, and a lot of them were interested in constructing stuff, and so we connected that to the environmental theme, and we just scavenged. We’d take the dolly out on garbage day, and we’d roll it around and grab stuff and then come back and create things. I found it was a way to pull in kids who wouldn’t normally be successful in school. They’d have some success, and that enabled them to be successful in other subjects.

Adam: I got surplused from my school and placed here. But interestingly, the union rep who was at the meeting saying I was surplused knew that I was interested in alternative schools and actually mentioned that it was probably going to be a good fit for me, and to a certain degree I’d agree with that. Just recently, I had a student visiting, and she mentioned that she was telling her friends that she wants them to come here. She told them that she reduced the amount of therapy that she was getting from three days a week to one day a week. Despite the fact that I didn’t seek to be in an alternative school, it has worked out quite well in terms of what I can offer students, meeting certain needs that aren’t necessarily based on the class or the curriculum or school textbooks.

Sean: I’m not from this school. I’m essential staff. I applied to it. I’m special education. So it’s an interesting example of how alternative schools are both separate, but also part of the Board. They do have a social worker coming in, and I’m sure they’d like to have more, as all the schools would, but they have spec ed support here. My role here is to support spec ed students and to go from school to school. Any student who has an individual education plan, they’re a special education student. Generally, a school has twenty-five percent of its population spec ed, and alt schools are too small to have their own spec ed department, so I function as a mobile department for four different schools. There’s a number of staff like me and each have anywhere from two or three or four schools, depending on the size of those schools. So I’m at a different school every day of the week. They’re all alternative schools, and they’re all very different. I think because of that, I tend not to use the phrase “alt school”. I just call the schools by their names, because they’re not alike at all. They’re more un-alike than alike, I would say.

Ariel: That’s definitely what we’ve found in doing this project. We highlight the uniqueness of each one. And at the same time, we do look for commonalities, for what sets all of these schools apart from the mainstream.

Jeff: I think the commonality that you often see is size. It’s a simple thing. I mean, we’re small, right? And all of our kids are coming from giant schools with a thousand-plus students. The fact that we’re small even in itself is helpful. There’s a sense of community you might not have in larger high schools. Plus, there’s students coming to our school—it used to be they were coming here for the social justice focus, or the course content, or an alternative education, but now we’ve found that the big draw is that they are suffering anxiety and depression and all this stuff, and they need something a little more comfortable. I’m seeing that at a lot of the alternative schools, hearing that anxiety word all the time.

Ariel: So do you think that’s a larger social shift, and alternative schools are stepping into the breach that that’s opened up?

Jeff: Yes. And interestingly, we’re not experts. I mean, we just have some experience in mental health issues now by virtue of the fact that many kids with those concerns are coming here. So we do our best. We’ve always made students feel important and given them some one-on-one time, and that’s the big thing that we can offer. Every kid develops differently. It’s a challenge.

Beth: I think, too, we spend a lot of time developing a sense of community. We put a lot of emphasis on giving them food, so we’ve included cooking courses, and all staff members clean the kitchen and do the laundry. That’s a big part of what we do to make them feel comfy. We have therapy dogs that come. We do all kinds of stuff like that.

Sean: I see food at all the schools that I’m at. It seems minor, but it’s not. The students call the teachers by their first name. It seems like small change, but it actually does have a calming effect.

Ariel: Those are big things—breaking bread together and treating one another as equals.

Sean: Yeah, I think it sort of repersonalizes students after years of being depersonalized.

Claire: I’ll talk about how I came here. I think I’m the last one. I came pretty much right out of teacher’s college. I’d been recruited back in the days when there were teacher shortages, so they actually came to our school to recruit me for summer school. It was absolutely horrible. I had to do grade 12 English upgrading. I had two classes, forty-five students each, one in the morning, one in the afternoon. I went home and marked for seven hours. So at the end of that, I thought, “I don’t know if I’m going to survive this career.” And then I wasn’t hired in September, but I got hired in October when Val, a teacher at the first alternative school where I worked, was going off on maternity leave. That was my first job before this one, and I have been here since then, so it’s twenty-seven years ago. I’ve been bumped a couple of times, but always pulled back, and I often think that if I had ended up in a regular high school, I don’t know if I would’ve continued this career. Based on my teacher’s college placements, which were all in very mainstream, academic schools, I wasn’t really sure if this was going to be a good fit for me.

I’m actually a high school dropout myself. I never completed high school. So it’s interesting. I just applied to university as a mature student when I was twenty-one. I’d been out of high school for years. I’d been working, and I really think that if I had had a school like this one, I would’ve finished. I was in Ottawa, where there wasn’t a choice other than mainstream schools. If I had come here when I was seventeen, I wouldn’t have had all the setbacks I had. So I felt that this was the place that I needed when I was that age, and luckily I’ve managed to stay here all of this time.

But some people I do know from my graduating class from University of Toronto haven’t stuck it out. I think the dropout rate for teachers in the first couple of years is probably pretty high. I mean, it’s pretty brutal. Even here, I thought, does this fit? I just figured I’d stay ’til I paid off my student loan. By the time I paid off my loan, I thought, well, maybe ten years, and then it gets easier.

Maddie: I think being a high school dropout is a very useful thing. I think a lot of us were.

Claire: I see my students and I think, “Oh, my God, I just wish I could impart to you the wisdom that I have now. I was you. I was you forty years ago, and I wish I could explain to you that it can be different.” So I think I do have that identification with my students. I hated high school, but I would’ve loved this high school. My daughter ended up going to alternative schools, she went to Delta in grade 7 and 8, and she was at Inglenook. Now she’s a tattoo artist. [laughs] She’s making a good living doing it. She was always very artistic. She’s still friends with all these people she went to school with, who are all doing really interesting things.

Ariel: It’s funny you mention Inglenook, because you said how long you’ve been teaching, and I thought of Rob Rennick.

Claire: Yeah.

Ariel: He’s been there for about 30 years, is that right?

Claire: Yeah. He’s still there?

Ariel: He’s still there.

Claire: Because it was Rob and Bob. So Bob…

Michael: Bob retired.

Claire: Bob retired the year after my daughter was there. That’s some time ago now. But she had a great time there, met great, interesting people. But I just wondered if I had ended up working at Runnymede Collegiate or somewhere, whether I’d be doing something other than teaching now. I really felt, in my first years of teaching, that I might want to do something else, because teaching is scary, it’s brutal. I worked every weekend. I remember my partner getting up at two in the morning to go to the bathroom, and I’d be sitting there, cramming on the French Revolution. “What are you doing?” “I’ve got the French Revolution tomorrow, and I don’t have a clue.” Those first couple of years were a blur. All I remember was I would work every night at least ’til two in the morning, and then I would start working at noon on Saturday to get my preparation done. I was doing American History, Canadian History, History of Western Civilization, Writer’s Craft, Twentieth Century History. But I still felt this was the school that I wanted when I was this age. So sometimes I’m really frustrated by some of these people. I think, “I could save you a good five, ten years of grief, if I could just telepath to you what I’ve figured out.”

Sean: Some people need to experience the grief, though.

Claire: Yeah, they do. They do, to get there.